Budget cuts could prevent the country becoming open defecation free by 2019.

Published on: 21/03/2018

Note: This blog is based on text written by Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA), India. It has been edited and adapted for non-Indian audiences. Read the original text below under Downloads.

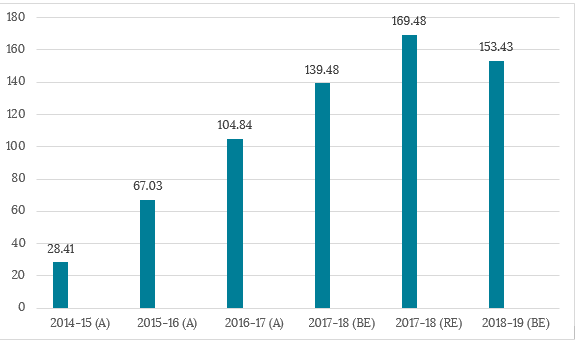

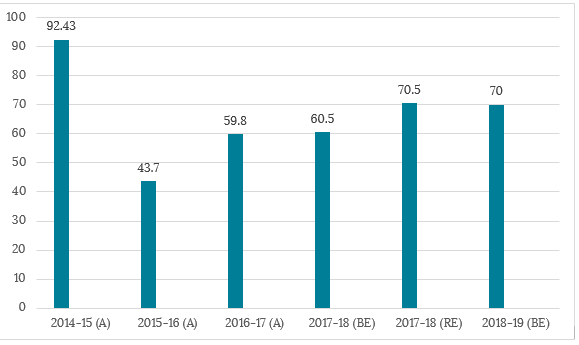

India’s rural water and sanitation sector eagerly awaited the 2018-19 budget since this is the last year of the five-year term of the current government. The country’s flagship Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) programme - or Clean India Mission in English - has invested more in sanitation than all its predecessors and has tremendous political backing. Surprisingly, allocations for rural water and sanitation turned out be around 7 percent less than last year. Compared to the 240 billion rupees (US$ 3.7 bn) that the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation (MDWS) received in 2017-18, it has allocated 224 bn rupees (US$ 3.4 bn) for 2018-19: 153 bn rupees (US$ 2.4 billion) for the rural sanitation programme and 70 bn rupees (US$ 1.1 bn) towards the rural water programme. The MDWS is the nodal agency involved in funding the SBM programme for rural sanitation and the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRWP) for rural drinking water

Lauding the progress made in the ambitious Swachh Bharat Mission, the Finance Minister in his 2018 Budget speech on February 1st, announced the government’s plans to construct around 20 million toilets, while claiming that 60 million had been already constructed under this mission. He also announced a new rural sanitation scheme called Galvanizing Organic Bio-Agro Resources Dhan (GOBAR-DHAN). This scheme addresses the solid- liquid waste management problem in villages by converting cattle dung and solid waste in farms to compost, fertiliser, bio-gas and bio-CNG (compressed natural gas). In a post-budget radio speech Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that the GOBAR-DHAN scheme will include an online trading platform to connect farmers with buyers of dung and agricultural waste.

With more than double the allocation since 2010, India's drinking water and sanitation ministry is on a roll. However, are there still enough funds for rural water supply and sanitation?

Source: Compiled by CBGA from Expenditure Budget Vol. 1 and 2, Union Budget, various years, GoI

Note: A – Actuals (expenditure made), BE – Budget Estimates (budget allocated at beginning of the financial year), RE – Revised Estimates (mid-year budget revisions in allocation).

There are enough reasons to cheer for the SBM (Rural) programme, as evident from government reports and coverage data. However, the Standing Committee on Rural Development has repeatedly pointed out that there is a shortfall in funds for the programme to meet its goal by 2019. The 2016 Report stated that the funding to the programme should be "suitably enhanced in a big way." In fact, the Ministry had demanded 250 bn rupees (US$ 3.8 bn) for the year 2017-18, but only received 140 bn rupees (US$ 2.1 bn). Hence, you wonder why instead of increasing the fund allocation for the rural sanitation programme, it was in fact reduced to 153 bn rupees (US$ 2.4 bn) in 2018-19 from 169 bn rupees (US$ 2.6 bn) in 2017-18 (fig 1).

Rural sanitation is not just about meeting toilet construction targets but also involves sustainability and usage. With the gradual reduction of budgets in the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP) (fig 2.), how sustainable will sanitation be without water? The preference for large containment structures continues to persist, leading to the overall cost of toilet construction becoming higher than the subsidy amount of 12,000 rupees (US$ 184). Is the reduced budget sufficient to make up for the resource gap that the Ministry is facing?

Source: Compiled by CBGA from Expenditure Budget Vol. 1 and 2, Union Budget, various years, GoI

Note: A – Actuals (expenditure made), BE – Budget Estimates (budget allocated at beginning of the financial year), RE – Revised Estimates (mid-year budget revisions in allocation).

We barely manage water for domestic use, water for toilet would increase our burden

Surely, the sustainability of the impact of the national sanitation programme (SBM-Rural) cannot be seen in isolation but should be linked to the water programme (NRDWP). Indians won't use toilets if there isn't enough water for cleansing. Hence the reduced budgets would be negatively impacted with the reduction in allocation. Self Help Group members in Arjipalli, Odisha said "We barely manage water for domestic use, water for a toilet would increase our burden to collect more water. For open defecation we use 1 litre, for using a toilet we will need at least 5 litres of water."

This year's budget for the rural sanitation programme should have been increased otherwise India will not reach the ambitious target of becoming open defecation free by 2019.

IRC welcomes guest bloggers who want to share their ideas and experiences on the IRC website. You can send in a request to communications@ircwash.org

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.